THE RESCUERS is an unusual documentary about the Holocaust. The story of the virtually unknown heroic diplomats who saved tens of thousands of Jewish lives during World War II is told through the eyes of Stephanie Nyombayire, a young Rwandan anti-genocide activist who lost over one hundred members of her family to genocide in her country, and is directed by a non-Jewish African-American. The film also features internationally-acclaimed historian Sir Martin Gilbert, who serves as Stephanie’s guide and mentor through their journey as they explore and contemplate the past in a quest, in part, to understand what should be done to stop the ongoing genocide in Darfur and elsewhere.

THE RESCUERS came to life after director Michael King received a call from his friend executive producer Joyce D. Mandell, about the diplomats. A businesswoman and philanthropist, Mandell first became aware of the story when she got involved in bringing a photography exhibit about the diplomats to the University of Hartford. She saw the exhibit again when it was shown at the Legislative Building in Washington, D.C. and on Ellis Island. She comments, “I felt this compelling story needed to be told to a much broader audience so I spoke with Michael because a documentary would make for a gripping account of this virtually unknown story.”

THE RESCUERS came to life after director Michael King received a call from his friend executive producer Joyce D. Mandell, about the diplomats. A businesswoman and philanthropist, Mandell first became aware of the story when she got involved in bringing a photography exhibit about the diplomats to the University of Hartford. She saw the exhibit again when it was shown at the Legislative Building in Washington, D.C. and on Ellis Island. She comments, “I felt this compelling story needed to be told to a much broader audience so I spoke with Michael because a documentary would make for a gripping account of this virtually unknown story.”

“Joyce invited me to Connecticut to meet with what I call ‘the committee’ that would serve as quasi-advisors on the film. It was comprised of a professor of Judaic Studies, a Rabbi, a Jewish Community Center executive director, a museum film curator, an author of books of Jewish History, various historians, and others knowledgeable about this time period. I had to pitch my idea and explain why I, an African American, was interested in the Holocaust,” states King. “My answer was simple. All of my films deal with social issues. As an African American male I have an understanding of crimes against humanity. If Steven Spielberg could make the film THE COLOR PURPLE, why can’t I make a film about the Holocaust? The idea with this film is to look at the Holocaust from a different perspective – from a present-day point of view through the eyes of a young girl from Rwanda. We wanted to tie the past to the present, which would make it a more universal story.”

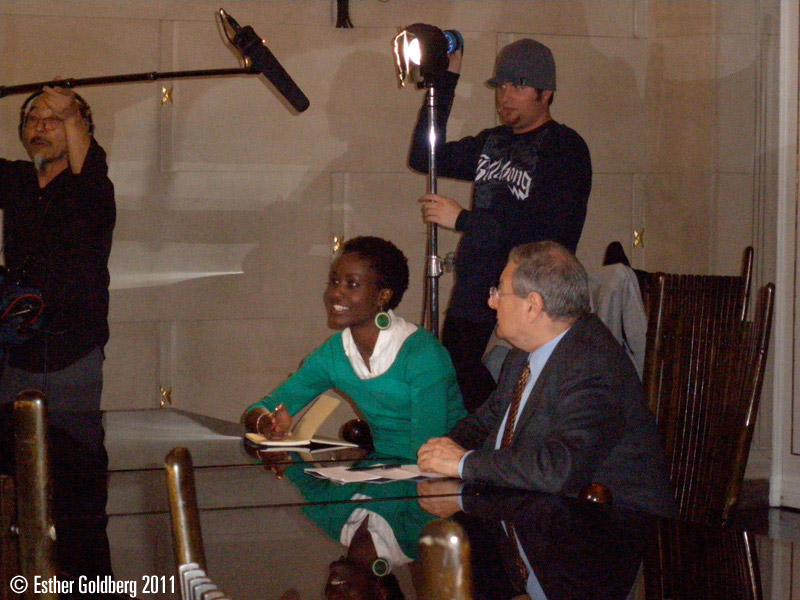

Because King was committed to not only telling the story of the diplomats, but also to ensure that the film would connect with a broader and younger audience and look at how the lessons from the Holocaust and the diplomats can be applied to modern day, he found Stephanie Nyombayire, a young Rwandan anti-genocide activist and co-founder of the Genocide Action Network who had lost family in the Rwandan Genocide. She notes, “I was immediately interested and excited about a project that focuses on the actions of those who stood up for what they believed in and the potential that this story could have to inspire those who are standing by to stand up against genocide.”

In searching for a narrator and someone to serve as Nyombayire’s guide through the film, King found Sir Martin Gilbert, one of the world’s pre-eminent historians on the Holocaust, who lost many family members during the Holocaust. King flew to London to meet Sir Martin and discovered that coincidentally, the historian had completed his book The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust, about ordinary people who saved Jews during the Holocaust, and was working on a book about the “Righteous Diplomats” who saved Jews that he’s hoping to finish next year. Sir Martin agreed to participate in THE RESCUERS and his involvement helped open doors across Europe that would prove to be critical in building the film. “I had written about these diplomats, but never met them,” Sir Martin comments. “The film gave me that precious opportunity.” Nyombayire adds, “Sir Martin is a very private man, but as time went on I think the 60 years since he lost many of his family members became closer and closer. I admire his strength and dedication in retracing the steps, the history, and the reasoning that led to the justification of the killing of his family and those who could have been his friends. Throughout the film he remained as generous with his knowledge as in the beginning, and toward the end he was able to share his personal story in a manner that showed that only a part of him had healed and that he was still struggling to accept that such a tragedy happened on such a scale.”

She continues, “From Sir Martin I learned about the role of history in shaping who we become. I learned that it’s in our hands to document its course so that it is understood and no longer repeated.”

With Sir Martin on board, King flew to Jerusalem and began his extensive research at Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. There, he had access to files of the Righteous Diplomats, which contained testimonials of the people who were rescued and ultimately saved. With the help of Irene Steinfelt, director of the Righteous Department, King was able to acquire the names of the diplomats’ descendants, and Holocaust survivors who had been saved by the diplomats, and was then able to meet and interview them. From that point, King fine-tuned the treatment and narrowed down who would be in the film and how the story would be told. “I spent three months researching, immersed in the subject, and becoming very intimate with it,” King says.

With Sir Martin on board, King flew to Jerusalem and began his extensive research at Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. There, he had access to files of the Righteous Diplomats, which contained testimonials of the people who were rescued and ultimately saved. With the help of Irene Steinfelt, director of the Righteous Department, King was able to acquire the names of the diplomats’ descendants, and Holocaust survivors who had been saved by the diplomats, and was then able to meet and interview them. From that point, King fine-tuned the treatment and narrowed down who would be in the film and how the story would be told. “I spent three months researching, immersed in the subject, and becoming very intimate with it,” King says.

Steinfelt says of the diplomats, “They are a very small group in the group of Righteous, but they’re a special group. They were the ones who disobeyed their superiors, who broke all of the rules, and who acted in contradiction to everything they were supposed to do. In normal times this is something we would never recommend, but here, this is what made them so special.”

From the beginning, King was upfront with all of the possible subjects in the film. “I told everyone that I was African American and also about Nyombayire. There’s no question that Sir Martin’s reputation and credentials added to our credibility,” King states. “I described the concept for the film and the idea of the mystery of goodness and what leads one person and not another to do the right thing. But I still had to gain their trust so that I could tell their story correctly because I was dealing with a history that was not related to me. To get them to trust me enough to open up, tell their story and relive the past was no small feat. I feel very privileged to have accomplished that.”

King continues, “At the same time, though, I believe this story can only enrich one’s life and empower one to do more as a human being. Who wouldn’t want to be part of that? Who wouldn’t want to tell his story to help inform the future? It was an easy pitch in that regard.”

Thirteen diplomats are featured in THE RESCUERS. The criteria used to select them were threefold: King explains, “We chose diplomats who saved the greatest number of lives; we looked at the emotional and dramatic elements of each story; and finally, I wanted to break some stereotypes. We do this in particular with two diplomats. One is Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, who was a member of the Nazi Party who was the German Attaché in Copenhagen and responsible for shipping the country’s Jews to Germany. Instead, Duckwitz arranged for the Swedish Prime Minister to agree to take in the Danish Jews. He organized the rescue of 7,200 people, which was an amazing act of goodness from someone who was a member of the Nazi Party and trained in the art of evil. We also include Selahattin Ulkumen, a Muslim diplomat who was the official Turkish Consul on the Greek Island of Rhodes, and ultimately responsible for saving generations of Jews.”

King continues, “It was in this way that I drew on my background as an African American and my desire to promote a multicultural society.”

Nyombayire adds, “From these diplomats I learned that one man or woman can make a difference and that in each of us there must exist the ability to reach within ourselves for the strength to do what we know is right. I firmly believe that most ordinary people who know killing one’s neighbor or child is wrong – it’s the inability or lack of courage to step away from the crowd that has allowed for mass crimes to be supported by ordinary individuals. From the diplomats I learned that we can begin to see the kind of impact joining hands with those individuals who aren’t bystanders can have.”

Nyombayire adds, “From these diplomats I learned that one man or woman can make a difference and that in each of us there must exist the ability to reach within ourselves for the strength to do what we know is right. I firmly believe that most ordinary people who know killing one’s neighbor or child is wrong – it’s the inability or lack of courage to step away from the crowd that has allowed for mass crimes to be supported by ordinary individuals. From the diplomats I learned that we can begin to see the kind of impact joining hands with those individuals who aren’t bystanders can have.”

She continues, “Contrary to common belief, people can put others before self and sacrifice for people they barely know. When one uses his or her privileges for the service of others, the ripple effects are beyond imagination as exemplified by the families of those who were saved by the visas.”

Mehmet Ulkumen, the son of the Turkish diplomat says, “My father said, ‘It is one man’s duty to help his brother. They were my brothers, so it was my duty to come to their assistance because I was in a position to do so’.”

Because of the subject matter, the process of making THE RESCUERS was a challenging experience emotionally for the entire crew, but for Sir Martin and Nyombayire in particular. Sir Martin says, “I have been involved in making films for more than 40 years. This was by far my most emotional filmmaking experience. I was again and again overwhelmed by the depth of the tragedy, as we saw so many of the places where Jews had been murdered. The greatest challenge was confronting the reality of the scale and force of evil. What helped get me through, however, was realizing that it was important to tell the story of the rescuers.”

During the film, Nyombayire is forced to face some painful truths. She interviews Lieutenant General Romeo Dallaire, former Force Commander of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Rwanda. Dallaire states in an in-person interview with Nyombayire about the U.N.’s position, “When the genocide started, my mandate as a U.N. Peacekeeper ended. There was reticence to get into another exercise in Africa, because they had just had Somalia a few months earlier and that was a debacle. The U.N. didn’t want to get into another African complex problem and was trying to do it on the cheap. Hopefully it would resolve itself. So it meant that Rwanda, Black Africa, didn’t count.”

Nyombayire talks about her reaction to sitting in that interview and hearing those words. She states, “What went through my head was that not much has changed. As we continue to watch history repeat itself in Darfur, it’s clear that some deaths represent less than others. I don’t necessarily believe it’s a question of race. It’s more a question of where the interest of the so-called international community lies. At the time of the Rwandan genocide, it did not lie in saving 1 million innocent lives.”

Nyombayire continues, “It was chilling to see not only how meticulous the preparation of the Holocaust was, but how much people do not learn from history. The dehumanization and preparation of the Holocaust is very similar to the one of the Rwandan genocide, as well as the rhetoric used to encourage the killings of Darfurians. It was baffling to go to Wannsee Villa and see the same kind of preparation that is now being uncovered about Rwanda. It gave me the mental image of how preparations must have proceeded in order to convince ordinary Rwandans that their friends, neighbors and family members deserved to be killed. It was even harder to face the reality as we’re learning about history, the people of Darfur have been faced with similar circumstances for more than five years, and the reaction from the international community has in fact not changed.”

As Nyombayire and Sir Martin gathered information about the diplomats they gained a deeper understanding of the work that went on behind the scenes to orchestrate both the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide. Nyombayire says, “The loss of my family made the memorials more personal, and imagining the dehumanization and cruel death of my family members made the lack of action from the international community more unbearable.”

She continues, “As one of the lucky Rwandans who was not in the country, I don’t consider myself a victim of unlearned lessons. However, my family was. They were victims of not only unlearned lessons, but also of ignored warnings and pleas for help. I believe that is the worst part – that the genocide wasn’t an overnight occurrence and that there was a possibility to stop it and save hundreds of thousands of people. My family and 1 million other Rwandans were not only killed because lessons weren’t learned, but also because of a purposeful decision by the United Nations not to take action.”

In addition to the emotional challenges, the logistics of shooting THE RESCUERS was extremely difficult. It was a 60-day shoot, across 15 countries and three continents, with 20 people in the production, travelling by train across Europe, with 40 boxes of equipment. King states, “We had to deal with visa problems, theft, and as we were travelling everywhere by train, sometimes they were late, or broke down. We ended up having to take a bus from Bordeaux to Biarritz with all of the equipment and people. It was very trying on everyone. Because of the layout of some of the stations, with tunnels and stairs to exit, it was sometimes 1/8 mile to exit carrying these great loads. After a few stations like this, we decided to rent a truck and driver and had the equipment meet us separately. I respect the entire crew’s strength and motivation in taking this journey to tell this story.”

THE RESCUERS explores the mystery of goodness, but since those who displayed such amazing acts of kindness can’t tell us in their own words why, we can only speculate. Sir Martin says, “There are good people and there are bad people. The good people may act from religious belief, from the guidance and example of their parents, or from a deep personal understanding that there is such a thing as decency, and that there is such a thing as free will: to act according to one’s conscience even if the consequences may be hard. Education can instill a sense of ethics, and so can upbringing and religion: these are the three basic strengths of civilization. The rescuers showed just how effective those strengths can be.”

King adds, “How could others stand by and watch, as so many of them did? That’s what makes it a mystery. It’s the concept that I wouldn’t let this happen to my family, so why would I watch this happen to another family and not try to prevent it. These stories are worthy just based on the humanitarian aspect of each of these individuals. These are the types of values and people we should want to introduce to our children and into our school system. For so long they weren’t honored. They went back to their countries and most ended up demoted and rejected for their actions, because they went against their country’s policy. Can you imagine, being penalized for saving thousands of lives?”

He continues, “These diplomats are hardly known today because after the war they didn’t brag about what they did, or get book deals. Their actions weren’t based on self-interest, self-gratification. It was the right thing to do and they weren’t looking for payback or recognition.”

“My hope is that through this story we can inspire others to ask themselves why goodness is a mystery and not the norm. This experience has given me the determination to continue to find ways through which we can ensure that genocide or attempts to commit genocide become history,” Nyombayire adds. “It gives me hope that if individuals could put their life, career and family at risk to save others, maybe this could become the norm rather than the exception.”

Remarkably, King was good friends since childhood with Billy Bingham, son of Hiram Bingham IV, who served as Vice-Consul at the American Consulate in Marseille, France. He, along with Varian Fry, saved tens of thousands of Jews including Marc Chagall and other artists and writers. “We were in school together from elementary school into college. No-one, including Billy, knew what his father had done until after he died,’’ King says. “They knew he was a diplomat, but that’s it. When he died, they found a box behind the fireplace containing letters and papers from people he had saved. That bewildered me. Why would someone who did such an amazing thing be silent about it, not even telling his family?”

King concludes, “That generation went silent. The war was over, they moved on. It’s human nature to not want to talk about it – ‘I saved a lot of lives, but how many were lost?’.”

THE RESCUERS features an original musical score from Dutch composer Paul M. van Brugge, who has scored more than 70 feature films. The soundtrack is performed by the Sofia Soloists Orchestra of Bulgaria. For the music, King wanted a composer who could bring European sensibilities to the score. “Paul loved the project and his family had been forced to leave Holland, so he had a personal connection to the history.”

THE RESCUERS features an original musical score from Dutch composer Paul M. van Brugge, who has scored more than 70 feature films. The soundtrack is performed by the Sofia Soloists Orchestra of Bulgaria. For the music, King wanted a composer who could bring European sensibilities to the score. “Paul loved the project and his family had been forced to leave Holland, so he had a personal connection to the history.”

To differentiate the sound throughout the film, van Brugge incorporated the traditional instrument from each county. “For each of the diplomats’ story, we used the instrument that was specific to the folklore of his country,” King comments. “This helped create a different and more diverse soundtrack.” The instruments used were: Guitar for Spain and Portugal; Accordion for France; Koto and Taiko for Japan; Bouzouki and Saz for Turkey; Lur –like instrument for Denmark; Banjo for England; Clarinet for Poland; and Cymbalon and Violin for Hungary.

In looking to the future, there is a reluctant sense of optimism. Mandell says, “We hope THE RESCUERS will produce global discussions about the issue of genocide. Genocide is a political issue, and power, politics, corruption and greed produce monstrous consequences.”

Sir Martin adds, “One can only hope that at the beginning of the 21st century when there is still so much persecution, that modern diplomats and individuals will be inspired by this story to take the same risk, the same initiative, if necessary, to sacrifice their own careers, so that humanity will not be betrayed again by evil, so that good will prevail.”

And finally, Nyombayire says, ‘”My life and my work are very centered on the subject matter of this film. As a current Master’s student in Public Policy and Administration, I plan to continue working on many forms of genocide prevention – which I believe is what the diplomats took into their own hands. I hope these stories will show that history isn’t made by an external force but it is in fact the addition of all our inputs into society. We have the opportunity as the first interconnected generation to look beyond our difference and to our common humanity and not only say, but ensure that it is unacceptable for anyone, anywhere to be killed for who they are. This is the lesson that I hope to apply in my everyday work and live.”

She concludes, “The same way genocide is always planned and executed by individuals, we can also plan and execute genocide prevention. We can take history and change into our own hands because as I mentioned in the film, evil only occurs as a result of good men and women staying silent.”